A design guru recently declared that the future of graphic design belongs to those who “read widely” and “develop good taste.” The first part is completely necessary, graphic designers should not only read widely, but also educate themselves across disciplines and fields. But the second? It’s dangerous. Because taste, unlike skill, is a cultural fiction too often rooted in privilege, repetition, and fear of ridicule.

So we ask: Good taste according to whom?

Taste is n ot universal. It’s inherited

Taste is shaped by where we grew up, what we were told was beautiful, and who we were taught to admire. When designers are told to “develop taste,” what’s often meant is:

- mimic the grid-based systems of early modernist design,

- align with the restrained minimalism of high-end branding,

- avoid expressive distortions that signal rebellion or imperfection.

But history tells a different story. Movements like surrealism, punk, or outsider art didn’t emerge from consensus, they emerged in opposition to taste.

“Good taste is the enemy of creativity.” — Pablo Picasso (a rebel with messy kerning)

When taste becomes a cage

Designers are often afraid to break the rules not because the rules are sacred but because the internet will punish them. “This isn’t aligned.” “That’s not legible.” “You’ve broken the grid.”

We forget that grids were invented. By humans. In a specific time. For a specific function. Not to become universal laws.

And yet today, many designers create work that is perfectly aligned, perfectly balanced, and perfectly boring. Because somewhere along the way, we mistook repetition for professionalism.

Taste is taught but should it be?

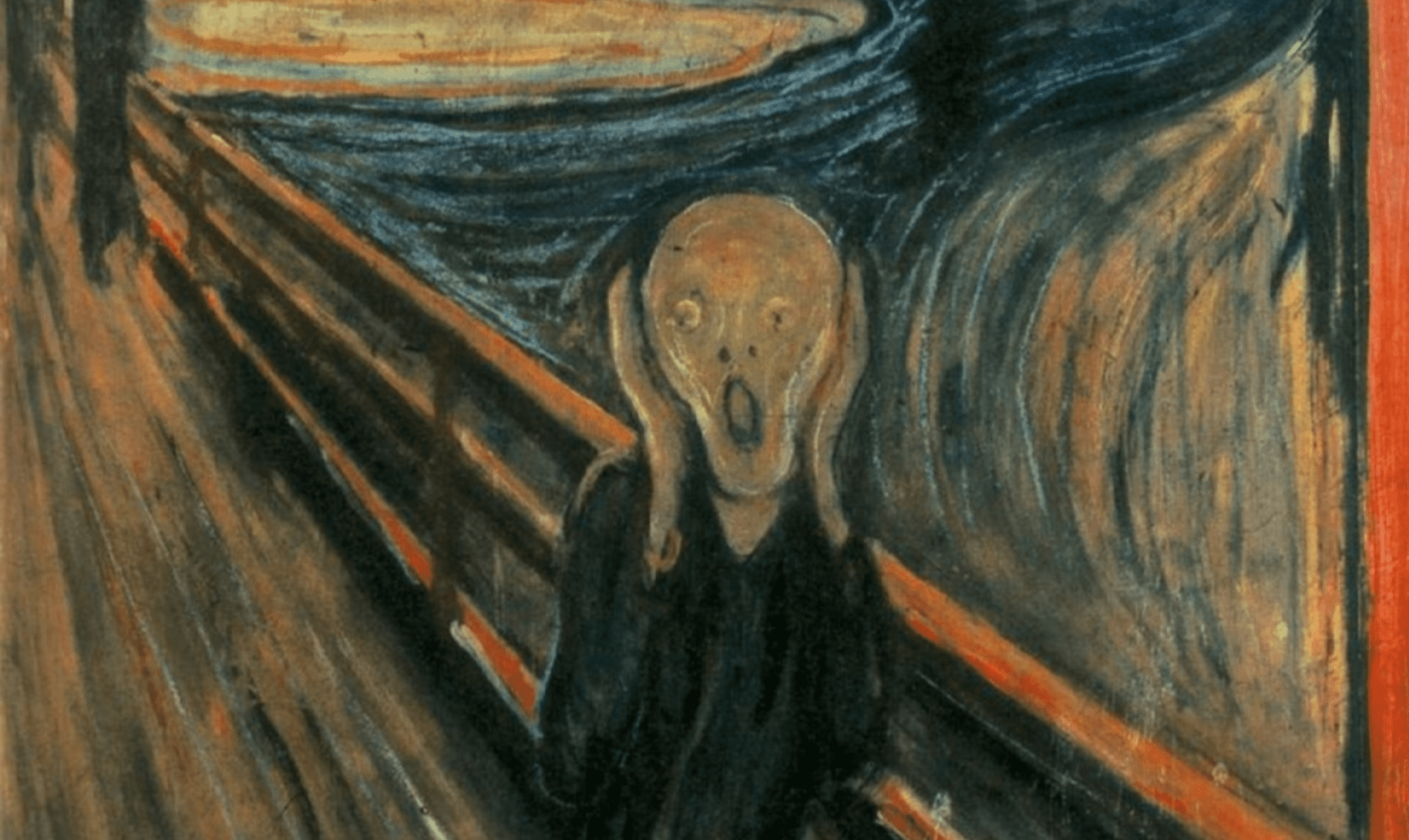

We once attended a public session where schoolchildren were shown several classic paintings. One girl rejected each one: “That one’s weird.” “That one too.” Then she saw The Scream by Edvard Munch. She stopped. “That’s cool,” she said. It wasn’t the most famous or the most perfect. But it felt alive and it spoke to her in a way the others didn’t.

Children are often taught what should be considered beautiful. But maybe they should also be taught how to challenge it. Or better yet, to develop a curiosity for contradiction.

Design without permission

Every movement that shifted design history was called ugly at first. Surrealism. Grunge. Brutalism. Even Bauhaus. If designers had obeyed taste, we’d still be drawing scrolls on parchment.

Taste is not a truth. It’s a trend. And trends don’t age well.

When taste decides what deserves to exist

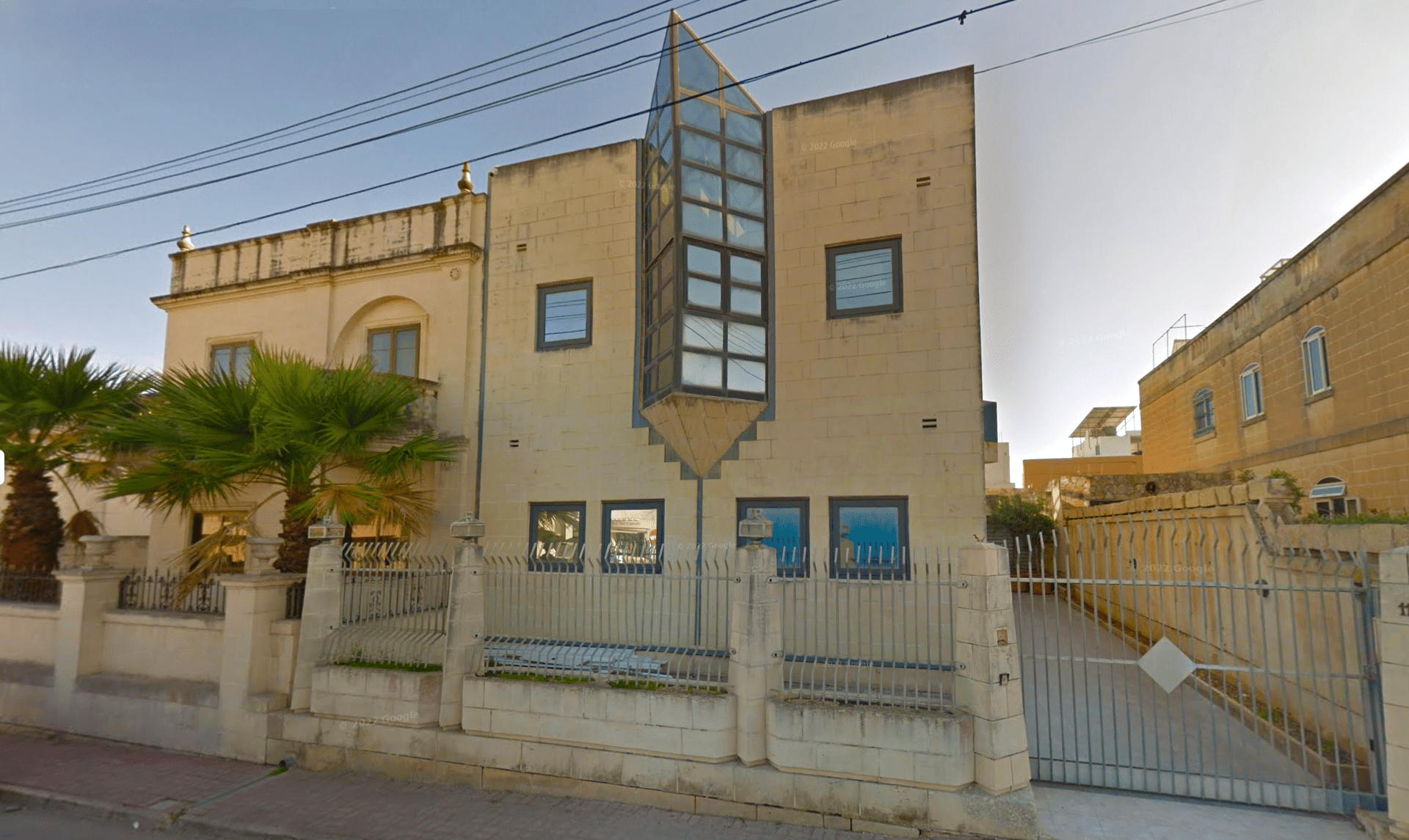

We attended a public conversation on whether to preserve or demolish an old building. One speaker shared the story of her grandfather an unrecognised artist in Malta who had designed that house as both home and studio. After his death, she moved in and found his lifetime of work: paintings, letters, books. None of it had ever been celebrated.

She now wants to turn the home into a museum. Not because it fits a national aesthetic, but because it mattered.

What stayed with us wasn’t the architecture. It was the question beneath it all:

What qualifies as cultural heritage… and who gets to decide?

Because taste isn’t just about logos or typography. It shapes memory. It tells us which artists matter. Which stories we save. And which buildings get to survive.

Final frame

When taste becomes a filter, we start designing for other designers.

When taste becomes a weapon, we erase voices that don’t “fit.”

When taste becomes gospel, we forget that design is meant to be felt, not worshipped.

So we ask again:

What if your ugliest idea… is your most original?

This isn’t the end of the conversation. Just the beginning of a better one.

A note to the brave

This is not for everyone.

This is for the ones who feel out of place. For those who’ve been told their instincts are too strange, their ideas too loud, their work too much.

To disobey good taste is not to court chaos. It’s to refuse a smaller life.

If you are different, own it. Stand up for it. Guard it like fire. Because if you hesitate, your energy splits in two and you’ll spend your life between jobs that don’t inspire you and ideas that never got made.

We’re tired of hearing “business as usual.” Of hearing “do what you are told.” Of accepting the idea that we’re victims of taste, of systems, of inherited limitations.

If being different, if being weird means being unfamiliar, uncomfortable, or hard to categorise, then normal must mean being passively shaped by what society has accepted.

This isn’t the time to shrink back. It’s the time to put yourself into the work. To believe in your input. Your instinct. Your contradiction.

Being different is not a liability. It’s the right choice.

And your weirdness? It’s not a flaw. It’s raw material.

What matters… is what you do with it.