Description

This case study focuses on the development on Goldsmith Street, Norwich, designed by London architecture studio Mikhail Riches, showcased as being a modern affordable social housing scheme of high architectural and environmental quality.1 In fact, this development consisting of 105 homes holds several awards, including the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) Stirling Prize of 2019 - which made it the first ever social housing scheme to win this prestigious prize, and described as a “modest masterpiece” by Julia Barfield, chairperson of the jury.

Strategy

The architects sought to re-think the design of social housing and, rather than building the bare minimum, incorporated ultra-low energy buildings and eco-technology built to the highest specification – enabling both the residents and the environment to benefit.

Perhaps the more obvious aesthetic approach the architects followed for this estate is its traditional street pattern, as opposed to the common, daunting block of flats. In addition to this, the design is less car-oriented, with parking shifted towards the boundaries of the estate and existing green links carefully integrated in the landscape scheme, extending beyond the site boundaries to include nearby roads and a park.

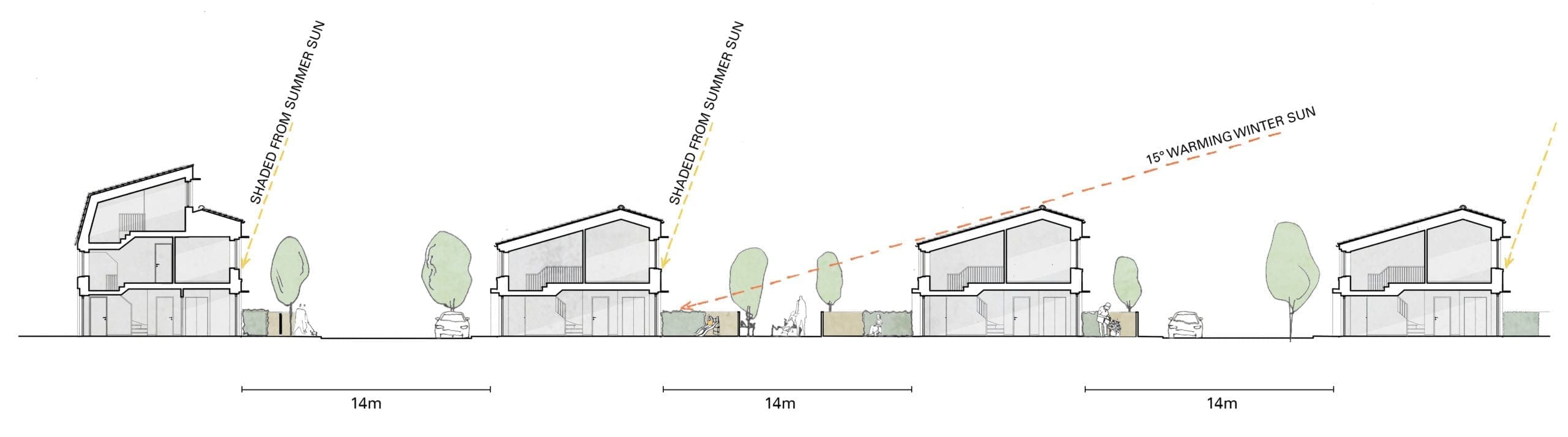

The terraced dwellings are spaced 14 metres apart, allowing it to be a high-density housing area. However, to avoid overshadowing, most of the houses are low-rise at two storeys high. While it may be the intention of developers to build new homes to the smallest size allowable, the architects designed these two-bedroom properties to be 90m2 – surpassing the 76m2 recommended by guidance for this type of property in the UK.

Photo credit: Mikhail Riches

Design Features

The project was “commended not just as a transformative social housing scheme and eco-development, but a pioneering exemplar for other local authorities to follow” says RIBA president Alan Jones.

The architectural language is contemporary with the corners of the houses curved to gently lead the visitors into the streets of the estate, while also serving as the envelope for internal staircases. The shared alleyways running through the centre of the estate, which are accessible from the private back gardens of the dwellings, provide residents with a communal garden and a safe area for children to play. Each dwelling has its own front and back garden2, and a different-coloured front door that leads onto the street, giving the residents a sense of ownership.3 These features place an emphasis on the social aspect of these developments, focusing on creating a community by reducing social isolation.

By aligning the street to have an East-West orientation, the designers ensured the homes have windows and habitable rooms facing South. This not only provides exposure to natural light, but also maximises the solar gains in winter and shade in summer, fitting within a passive solar scheme and greatly improving energy efficiency. Furthermore, the dwellings are fitted with internal heat recovery systems, walls that are over 600 millimetres thick, triple glazed apertures, and roofs that are inclined at an angle of 15 degrees to ensure the dwellings do not block sunlight from entering the windows of the adjacent properties.4

With their sharp attention to detail, the architects turned this project into a sustainable housing development that is now the largest social housing scheme that has achieved the Passivhaus standard in the UK.

These key design features significantly lower the heating and cooling costs by up to 70%, when compared to average UK homes.

Passivhaus

Properties that hold a Passivhaus standard, a very rigorous German regulations for environmental performance, have the highest certifiable standard of energy efficiency and result in ultra-low energy buildings. It is a system that puts the building fabric first; i.e. it uses the components that make up the building to reduce energy consumption rather than relying on the use of renewable energy devices. Passivhaus depends on five design pillars:

-

Super insulation

-

Thermal bridging

-

Stringent air tightness

-

Solar gain

-

Ventilation system

(Well not quite the thermos flask then; but you get what we mean) These key design features significantly lower the heating and cooling costs by up to 70%, when compared to average UK homes. The social houses belonging to this development on Goldsmith Street are quoted to have a yearly energy bill of approximately £150.

Contrary to common perception, projects of such a high specification need not necessarily be very expensive projects. Although this social housing scheme cost around 10% more than a typical procurement would have, when considering the whole-life costing, these properties result in a far more superior quality in terms of running costs, carbon emissions, comfort levels and health benefits. The long-lasting products and materials specified in this development do not require frequent replacement, implying that the additional initial costs will come down in the long run.

As the Passivhaus practice spreads geographically, increasing its exposure, the short-term costs will naturally decline as the market expands and the skills gap between design and construction diminishes. Case studies such as Goldsmith Street demonstrate that, given the right context, the learning from the Passivhaus practice can be passed on to improve the quality of other future non-Passivhaus projects.

The social houses belonging to this development on Goldsmith Street are quoted to have a yearly energy bill of approximately £150.

Photo credit: Mikhail Riches

Malta and Passivhaus

One may argue that the principles of Passivhaus are difficult to achieve. However, we can explore our vernacular typologies in a way that could accommodate our climatic condition. This way, the Maltese thermos flask will respond to our local needs. Windows play a huge part in the thoughtful balance between cooling and heating. These apertures are culturally significant, as we are people that look outwards to the horizon – the sea! Hence, one must ensure this line of visibility is incorporated when possible, as it also has a psychological factor embedded in its fundamental function. The best options for shading, window-glazing and exterior building colour need to be examined depending on the orientation and exposure of the building. Controlling gains and losses over different seasons needs to be carefully worked out. Colour plays a very important part in this as well-planned use of outdoor colours can change the cooling demand by up to 5 kWh/m² (7), even in well-insulated buildings. After all, the Maltese are used to a lot of light – it is a contrasting feature to other climates and what makes our seasons Maltese! When it comes to the interior spaces, the use of ‘cool’ colours on outside walls lowers solar absorption, helping to reduce the sun’s heat load during the summer months.

Moreover, moveable rather than fixed exterior shading is preferred to avoid additional heating demands in winter. Care must be taken to ensure that the permanent shading of east or west-facing windows does not increase the winter cooling load beyond any energy gains achieved from the same shading in summer.

Critique

Housing plays an important role in improving health and wellbeing, both in terms of the quality and affordability of housing as well as the quality of neighbourhoods and communities. Therefore, one way that housing design and housing policy can contribute to a good quality of life is by creating new opportunities for improved integration between housing, health and social care.

While this project deserves all the acclaim that it has had, it would have been ideal to hear more about the social dimension (other than the communal spaces) and if the community was involved in the design process. Design cannot stand on its own. It needs to be understood from a cultural perspective and accommodate the needs of the 21st century city dweller. It is imperative to ensure collaborations with all stakeholders and the community and, in essence, approach the design bottom-up, with the inhabitants of these buildings playing a much greater part in helping to shape buildings. After all, buildings shape us and we shape buildings!

The right type of homes in the right place at the right price to meet the housing need and to attract new businesses and investment in the city in turn will create new jobs and training opportunities, thus pushing toward a thriving city.